Wednesday, August 26, 2015

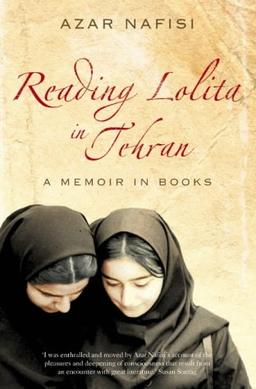

BOOKS: Reading Lolita in Tehran

When I think back on my school years, it is usually the English teachers who stand out as the most profoundly influential. I think this maxim would be accepted by the students of Azar Nafisi, author of the fascinating memoir Reading Lolita in Tehran. I was transported by her account of her years as a professor of literature at various universities in Tehran in the wake of the Shah's fall and the rise of the Islamic Republic of Iran. The book is a witness to the horror of how a rather liberal and educated society can so quickly transform into a totalitarian theocracy, and of the sometimes surreal life under such rule. I'd had a fairly shallow and monochromatic understanding of modern Iran, so this book was very illuminating for me in filling in rich detail how the Islamic republic first arose amidst a complex mix of Islamists and a more Marxist-inspired revolutionary movement, and later how things changed (or didn't change) through the war with Iraq, and the death of Ayatollah Khomeini. But what makes the book work so well is that it is not focused on politics per se, but on literature and the lives of a group of especially motivated students who continue to meet with Dr. Nafisi, even after she is pushed out of the university, in order to study the works of great novelists. Early on, when her students were pressing her for her approval of their urgent revolutionary ideals, she insists that she is neither for the Islamists or the Marxists, rather she is for Jane Austen and Henry James. At one point in her class, they even put The Great Gatsby on trial. The interplay between the themes and characters of classic novels with the lives and struggles of the women in Nafisi's private study group is fascinating, with each providing a mirror that shows the other in a new light. Her students share a common desire to study literature, but little else. Some are married, some are not; some are religious, some are not; and so on. Their varied experiences provide threads of many colors for Nafisi to weave into an exquisite Persian carpet of a memoir.

Sunday, August 16, 2015

STAGE: Bent

We saw some breathtaking theatre last Saturday at the Mark Taper, in their production of Bent by Martin Sherman. The play is a powerful, horrifying chronicle of gay life in Germany during the rise of the Nazis. It begins in the liberal, decadent Berlin of the 1930's (picture Cabaret), but where Cabaret merely gestures at the horror to come, Bent actually takes us there, as the play's protagonist, Max, goes on the run, is captured, and ultimately transported to Dachau. Max does what he needs to do to stay alive in the grip of captors with a vicious talent for treatment calculated to lacerate one's soul and strip one's humanity. There was a moment when Max was broken like Winston at the end of Orwell's 1984, yet this story goes beyond that moment as Max, through Horst, a man he meets on the transport, learns to rediscover and reclaim his humanity and dignity even in the face of evil. The arc of this story is heart-stopping, and the enactment of it that we saw on Saturday night was gripping. The performances were all electric and spot-on, particularly Patrick Heusinger and Charlie Hofheimer as Max and Horst, and Will Taylor as Rudy, and all the rest of the cast. The direction by Moisés Kaufman was fantastic, so creatively realizing this story, and pulling out all the stops of the theatre craft. The stage, lighting, and especially the sound were used to marvelous effect (such as creating a train just from sound and light).

This play originally premiered in 1979, illuminating the previously little-known persecution of gays under the Nazis, and establishing the pink triangle as a reclaimed symbol of gay pride. Thirty-five years later, it remains as relevant as ever. One of the most frightening things was just realizing how quickly a liberal society can be taken over by jackboots. Germany in the early 1930s was not so different from America in the 1970s or even now for that matter, and yet how quickly complacent liberals fell under the boot. (I'm currently reading a book that tells a similar story of Tehran circa 1980.) I know that several memorable scenes from this play will haunt me: the SS bursting into Max and Rudy's apartment, when Max is forced to betray his own love, the amazing scenes of Max and Horst making love without moving or touching each other, and the electrifying end.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)