With another off-Friday opportunity to explore my city, I headed down to Long Beach. For lunch, Cambodian food was on the menu. In one of those quirks of human migration patterns, the stream of Cambodian emigrants in the wake of the 1979 fall of the Khmer Rouge regime ended up concentrating in Long Beach, and creating a CambodiaTown along Anaheim Blvd. Arguably ground zero of CambodiaTown has been a place called Sophy’s (or also called CambodiaTown Food & Music), a restaurant but also a bit of market and community center. I’d been tipped off by Eater.com that a dish called amok trey was a great intro into authentic Cambodian cuisine. Amok trey is made from catfish fillets rubbed with kroeung -- a curry paste, and steamed with red and green peppers -- and some leafy veg with a stalk (similar to Chinese broccoli). The curry paste has similar ingredients to Thai curry - lemongrass, galangal, chili, kaffir lime - but a bit more sour than Thai. This fish was mild, tender, and delicious.

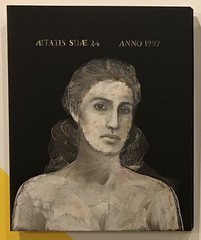

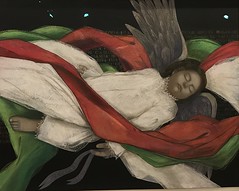

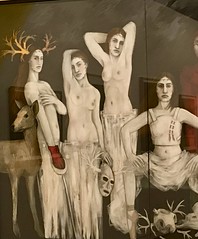

After lunch, my culture target was the Museum of Latin American Art, where a new exhibition of Judithe Hernández had just opened. I wasn’t familiar with the artist, but when I saw some of the striking images of her work, and when I learned that she was a cohort of Carlos Almaraz, whose work I’d really appreciated at a LACMA exhibit last summer, I knew I wanted to check it out. As the only female artist in the art collective Los Four, and one of the few female artists in the Chicano art movement at all, she developed a strong feminist identity expressed in her work. She works almost exclusively in pastel on paper, with figurative depictions of women, with a dream-like quality that conveys these women as archetypes to be read symbolically rather than portraits of specific actual women. A number of her works are set in vivid botanical landscapes, Rousseau-like jungle foliage or desert scapes, and some contain dream-like animals. This sort of magical realism will suggest comparisons to Frida Kahlo, but Hernández has her own clearly distinct style and vision. A number of the pieces express pointed commentary on contemporary events. One set, called the Juarez series, reflects on the spate of random murders of women and girls around Ciudad Juarez. There have been hundreds of these “feminicides” since 1993, with no apparent motive, just women violently killed, their bodies left in the desert. In The Unknown Saint, a ghostly woman on her back seems to float above a stand of cactus in the desert under a full moon night sky, a thin blood-red ribbon coiled around her grey neck and trailing off different directions into the expanse of desert. This large mural is hauntingly beautiful. In another part of the Juarez series, a trilogy of small portraits of women echoes a European Renaissance tradition of aetatis suae portraits, in which families with marriageable young daughters would have portraits painted, annotated with the age of the girl and the year, for circulation around society soliciting suitors. Here Hernández, in a biting riff on the classical form, has painted portraits of young women with their age and year of their untimely deaths. Another very recent work, reacting to then-candidate Trump’s comments on Mexican immigrants, draws on a Spanish Colonial tradition of dressing deceased infants in saintly garments. Her Death of the Innocents memorializes a young child lost to the dangers of attempts to cross the northern Mexican deserts to get the United States. The deceased child is dressed as a saint, with red and green sashes (colors of the Mexican flag), and holding a ribbon that says “we come but to dream”. Though mortality is certainly a prevalent theme in her work, it’s not entirely pervasive. Other works (like Jungle of Fire, The Birth of Eve, and Garden of Dreams) are vivid dreamscapes. Some are provocative in other ways. Les Desmoiselles d’Barrio is her feminist pastiche of Picasso's seminal work, Les Desmoiselles d'Avignon. Her desmoiselles are much more formidable, with luchadora (Mexican wrestling) masks, and some armed with rapiers. For Hernández, women have layers of masks. Even with their luchadora masks removed, these women's faces are identical, and appear stitched onto their heads.

After being immersed in the colorful dreamlands of Judithe Hernández, I stepped into the sunlight of the Gumbiner Sculpture Garden, where a collection of modern sculpture by Latin artists is set amidst cactus and palms. A few particularly caught my eye. I liked Gaudi Esté’s Perro Nagual con cara de conejo (rabbit-faced dog spirit), a figurative bronze howling at the moon. In Williams Barbosa’s Danza no 1, the curve and sweep of the two tall red iron abstracts had be thinking “Fred and Ginger” before I even saw the title. Carlos Luna’s comic War-Giro looks like a goofy sheriff from the front with his skeleton exposed on the back. Gustavo López Armentia’s Objetos del Mundo (objects of the world) is a monumental fork and knife with hieroglyphic-like symbology (more worldly objects) carved into them when you look up close. All in all, definitely worth the short drive down to Long Beach. (See complete set of photos from the day here.)

After lunch, my culture target was the Museum of Latin American Art, where a new exhibition of Judithe Hernández had just opened. I wasn’t familiar with the artist, but when I saw some of the striking images of her work, and when I learned that she was a cohort of Carlos Almaraz, whose work I’d really appreciated at a LACMA exhibit last summer, I knew I wanted to check it out. As the only female artist in the art collective Los Four, and one of the few female artists in the Chicano art movement at all, she developed a strong feminist identity expressed in her work. She works almost exclusively in pastel on paper, with figurative depictions of women, with a dream-like quality that conveys these women as archetypes to be read symbolically rather than portraits of specific actual women. A number of her works are set in vivid botanical landscapes, Rousseau-like jungle foliage or desert scapes, and some contain dream-like animals. This sort of magical realism will suggest comparisons to Frida Kahlo, but Hernández has her own clearly distinct style and vision. A number of the pieces express pointed commentary on contemporary events. One set, called the Juarez series, reflects on the spate of random murders of women and girls around Ciudad Juarez. There have been hundreds of these “feminicides” since 1993, with no apparent motive, just women violently killed, their bodies left in the desert. In The Unknown Saint, a ghostly woman on her back seems to float above a stand of cactus in the desert under a full moon night sky, a thin blood-red ribbon coiled around her grey neck and trailing off different directions into the expanse of desert. This large mural is hauntingly beautiful. In another part of the Juarez series, a trilogy of small portraits of women echoes a European Renaissance tradition of aetatis suae portraits, in which families with marriageable young daughters would have portraits painted, annotated with the age of the girl and the year, for circulation around society soliciting suitors. Here Hernández, in a biting riff on the classical form, has painted portraits of young women with their age and year of their untimely deaths. Another very recent work, reacting to then-candidate Trump’s comments on Mexican immigrants, draws on a Spanish Colonial tradition of dressing deceased infants in saintly garments. Her Death of the Innocents memorializes a young child lost to the dangers of attempts to cross the northern Mexican deserts to get the United States. The deceased child is dressed as a saint, with red and green sashes (colors of the Mexican flag), and holding a ribbon that says “we come but to dream”. Though mortality is certainly a prevalent theme in her work, it’s not entirely pervasive. Other works (like Jungle of Fire, The Birth of Eve, and Garden of Dreams) are vivid dreamscapes. Some are provocative in other ways. Les Desmoiselles d’Barrio is her feminist pastiche of Picasso's seminal work, Les Desmoiselles d'Avignon. Her desmoiselles are much more formidable, with luchadora (Mexican wrestling) masks, and some armed with rapiers. For Hernández, women have layers of masks. Even with their luchadora masks removed, these women's faces are identical, and appear stitched onto their heads.

After being immersed in the colorful dreamlands of Judithe Hernández, I stepped into the sunlight of the Gumbiner Sculpture Garden, where a collection of modern sculpture by Latin artists is set amidst cactus and palms. A few particularly caught my eye. I liked Gaudi Esté’s Perro Nagual con cara de conejo (rabbit-faced dog spirit), a figurative bronze howling at the moon. In Williams Barbosa’s Danza no 1, the curve and sweep of the two tall red iron abstracts had be thinking “Fred and Ginger” before I even saw the title. Carlos Luna’s comic War-Giro looks like a goofy sheriff from the front with his skeleton exposed on the back. Gustavo López Armentia’s Objetos del Mundo (objects of the world) is a monumental fork and knife with hieroglyphic-like symbology (more worldly objects) carved into them when you look up close. All in all, definitely worth the short drive down to Long Beach. (See complete set of photos from the day here.)

No comments:

Post a Comment