Le Temps Qui Reste (Time To Leave) explores the reaction of Romain, a gay man who has everything going for him -- a successful career as a fashion photographer, a lover, a supportive family -- and then discovers that he has terminal cancer. Rejecting the usual path of battling the cancer and fraught emotional goodbyes to his loved ones, he refuses treatment, tells no one, alienates those around him, and dies alone. If this sounds morose and a bit harsh, it is, and his behavior pushes away the sympathy of the film audience as well as the characters in his life. And yet the film does a great job of keeping Romain comprehensible and interesting. You come to realize that he is not a total jerk, but his actions are his way of being able to take his leave. The movie is very interior, and Melvil Poupaud does a tremendous job of conveying so much unspoken emotions of fear, anger, doubt, and wistful nostalgia. Director François Ozon deftly makes the interior exterior as Romain at times walks through his own past and confronts himself as a young boy. The moments of magical realism are woven seamlessly into an otherwise very real film. Romain's camera is used to good effect to signal the fleeting memories he'd like to capture. There are also some great interactive character vignettes, with his grandmother (Jeanne Moreau), his father (Daniel Duval), and his lover (Christian Sengewald), and a surprising sequence with a random waitress (Valeria Bruni Tedeschi). This is by no means a "feel good" movie, nor is it a tear-jerker, but it should make you think twice about the choices one might make in Romain's situation. Ozon has done a remarkable job of making self-alienation understandable and almost engaging.

Le Temps Qui Reste (Time To Leave) explores the reaction of Romain, a gay man who has everything going for him -- a successful career as a fashion photographer, a lover, a supportive family -- and then discovers that he has terminal cancer. Rejecting the usual path of battling the cancer and fraught emotional goodbyes to his loved ones, he refuses treatment, tells no one, alienates those around him, and dies alone. If this sounds morose and a bit harsh, it is, and his behavior pushes away the sympathy of the film audience as well as the characters in his life. And yet the film does a great job of keeping Romain comprehensible and interesting. You come to realize that he is not a total jerk, but his actions are his way of being able to take his leave. The movie is very interior, and Melvil Poupaud does a tremendous job of conveying so much unspoken emotions of fear, anger, doubt, and wistful nostalgia. Director François Ozon deftly makes the interior exterior as Romain at times walks through his own past and confronts himself as a young boy. The moments of magical realism are woven seamlessly into an otherwise very real film. Romain's camera is used to good effect to signal the fleeting memories he'd like to capture. There are also some great interactive character vignettes, with his grandmother (Jeanne Moreau), his father (Daniel Duval), and his lover (Christian Sengewald), and a surprising sequence with a random waitress (Valeria Bruni Tedeschi). This is by no means a "feel good" movie, nor is it a tear-jerker, but it should make you think twice about the choices one might make in Romain's situation. Ozon has done a remarkable job of making self-alienation understandable and almost engaging.

Thursday, July 27, 2006

FILM: Le Temps Qui Reste

Le Temps Qui Reste (Time To Leave) explores the reaction of Romain, a gay man who has everything going for him -- a successful career as a fashion photographer, a lover, a supportive family -- and then discovers that he has terminal cancer. Rejecting the usual path of battling the cancer and fraught emotional goodbyes to his loved ones, he refuses treatment, tells no one, alienates those around him, and dies alone. If this sounds morose and a bit harsh, it is, and his behavior pushes away the sympathy of the film audience as well as the characters in his life. And yet the film does a great job of keeping Romain comprehensible and interesting. You come to realize that he is not a total jerk, but his actions are his way of being able to take his leave. The movie is very interior, and Melvil Poupaud does a tremendous job of conveying so much unspoken emotions of fear, anger, doubt, and wistful nostalgia. Director François Ozon deftly makes the interior exterior as Romain at times walks through his own past and confronts himself as a young boy. The moments of magical realism are woven seamlessly into an otherwise very real film. Romain's camera is used to good effect to signal the fleeting memories he'd like to capture. There are also some great interactive character vignettes, with his grandmother (Jeanne Moreau), his father (Daniel Duval), and his lover (Christian Sengewald), and a surprising sequence with a random waitress (Valeria Bruni Tedeschi). This is by no means a "feel good" movie, nor is it a tear-jerker, but it should make you think twice about the choices one might make in Romain's situation. Ozon has done a remarkable job of making self-alienation understandable and almost engaging.

Le Temps Qui Reste (Time To Leave) explores the reaction of Romain, a gay man who has everything going for him -- a successful career as a fashion photographer, a lover, a supportive family -- and then discovers that he has terminal cancer. Rejecting the usual path of battling the cancer and fraught emotional goodbyes to his loved ones, he refuses treatment, tells no one, alienates those around him, and dies alone. If this sounds morose and a bit harsh, it is, and his behavior pushes away the sympathy of the film audience as well as the characters in his life. And yet the film does a great job of keeping Romain comprehensible and interesting. You come to realize that he is not a total jerk, but his actions are his way of being able to take his leave. The movie is very interior, and Melvil Poupaud does a tremendous job of conveying so much unspoken emotions of fear, anger, doubt, and wistful nostalgia. Director François Ozon deftly makes the interior exterior as Romain at times walks through his own past and confronts himself as a young boy. The moments of magical realism are woven seamlessly into an otherwise very real film. Romain's camera is used to good effect to signal the fleeting memories he'd like to capture. There are also some great interactive character vignettes, with his grandmother (Jeanne Moreau), his father (Daniel Duval), and his lover (Christian Sengewald), and a surprising sequence with a random waitress (Valeria Bruni Tedeschi). This is by no means a "feel good" movie, nor is it a tear-jerker, but it should make you think twice about the choices one might make in Romain's situation. Ozon has done a remarkable job of making self-alienation understandable and almost engaging.

Monday, July 24, 2006

Stem Cells and Animal-Rights Vegetarians

President Bush's first-ever veto, of a bill authorizing embryonic stem cell research, has flared up once again the debate about the ethics of such research. While a vocal minority of Americans object to this research as destruction of human life, I believe the majority of Americans are taking a more pragmatic view, that the tiny clump of cells called a "blastocyst" represents human potential but not human life, and it is reasonable to use them for life-saving research especially when they are going to be discarded anyway. This debate has not fallen cleanly down traditional political lines. When it was discussed on the NPR radio program Left, Right, and Center, the representatives across the political spectrum all agreed that embryonic stem cell research was worthwhile and not unethical.

The emotional debate about the ethics of the research tends to overshadow the actual question on the table, which is not whether such research should be permitted, but whether such research should be funded by the federal government. It's a different question. Andrew Sullivan (who himself opposes such research) has aired some interesting viewpoints. In one, a researcher notes that it is often not practical for a researcher to isolate his research and funding sources in a lab that typically supports a variety of research simultaneously. (His predicament called to mind those who take the kosher laws very seriously, such that they end up having to have duplicate sets of kitchen service and cookware.) In another, an optimistic libertarian opined that private funding sources already appear to be more than picking up the slack left by the federal non-funding, which is as it should be anyway. (Certainly, the federal funding void has created an opportunity for some states, such as my home state California, to gain a competitive advantage by funding research at the state level.) Given these developments, I'm somewhat sanguine about the President's veto.

I do think that the President's position seems reasonable. He does not advocate banning the controversial research. He merely advocates not having the federal government bankroll it when some taxpayers have moral misgivings about it. It seems a reasonable compromise for both sides. It does, however, raise a question in my mind. To what extent should the federal government not be engaged in practices that some citizens (even if just a vocal minority) have a strong moral objection to. Animal rights activists come to mind, those of the belief that all killing of animals is wrong, and carnivorous behavior is immoral. Such people are certainly a minority, but they also certainly have a very strong moral belief. Should the federal government therefore disengage in any direct activity or funding for activity that supports the meat industry? Should the feds stop providing meat inspection services and animal health programs (e.g., studying of "mad cow" disease and programs to prevent it)? This would seem to be consistent with the President's rationale on stem cell research. And of course the strong libertarians would agree with such a proposal -- not that they necessarily oppose meat-eating -- but that the government should not be involved in it. Food for thought.

The emotional debate about the ethics of the research tends to overshadow the actual question on the table, which is not whether such research should be permitted, but whether such research should be funded by the federal government. It's a different question. Andrew Sullivan (who himself opposes such research) has aired some interesting viewpoints. In one, a researcher notes that it is often not practical for a researcher to isolate his research and funding sources in a lab that typically supports a variety of research simultaneously. (His predicament called to mind those who take the kosher laws very seriously, such that they end up having to have duplicate sets of kitchen service and cookware.) In another, an optimistic libertarian opined that private funding sources already appear to be more than picking up the slack left by the federal non-funding, which is as it should be anyway. (Certainly, the federal funding void has created an opportunity for some states, such as my home state California, to gain a competitive advantage by funding research at the state level.) Given these developments, I'm somewhat sanguine about the President's veto.

I do think that the President's position seems reasonable. He does not advocate banning the controversial research. He merely advocates not having the federal government bankroll it when some taxpayers have moral misgivings about it. It seems a reasonable compromise for both sides. It does, however, raise a question in my mind. To what extent should the federal government not be engaged in practices that some citizens (even if just a vocal minority) have a strong moral objection to. Animal rights activists come to mind, those of the belief that all killing of animals is wrong, and carnivorous behavior is immoral. Such people are certainly a minority, but they also certainly have a very strong moral belief. Should the federal government therefore disengage in any direct activity or funding for activity that supports the meat industry? Should the feds stop providing meat inspection services and animal health programs (e.g., studying of "mad cow" disease and programs to prevent it)? This would seem to be consistent with the President's rationale on stem cell research. And of course the strong libertarians would agree with such a proposal -- not that they necessarily oppose meat-eating -- but that the government should not be involved in it. Food for thought.

Thursday, July 20, 2006

230 Years Ago, One Year Ago

I've been thinking a lot about the American Revolution lately, and having recently read David McCollough's 1776, and at the same time doing some family history research on ancestors who served then. Most recently, I've found the war pension files of a 5x-great-uncle which make a fascinating read. The file contains personal statements from both my uncle and aunt with some vivid description of what they endured. He worked much of the war for the commissary, which basically meant that he ranged the countryside around the Continental Army encampments in search of food and other provisions, begging, borrowing, or buying it (mostly on credit) as he could. McCollough described how many of the soldiers had old shoes or no shoes at all, as they marched through winter conditions. This was probably the case with my uncle, who froze his feet in search of provisions, an injury that afflicted him the rest of his life. At one point, his superiors had asked him to basically take a break, as his health was in jeopardy from his exertions. However, he felt an obligation to continue, thinking of the garrisons that were close to starvation. All this time, the men were often going long periods of time with no pay to support their families, yet they spoke repeatedly of "duty" and "public service", and dedication to their cause. His wife speaks of the hard times endured by the women, and the uneasiness of living among divided countrymen. Check it out here.

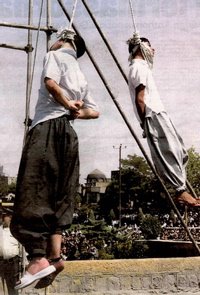

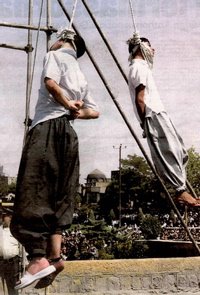

Understanding the tribulations our forebearers went through to establish this nation should make us appreciate all the more the great liberty that we enjoy here. This is put in stark contrast by thinking of those in the Middle East who are struggling to establish or defend democratic ideals against vicious enemies, and those who are living under oppressive theocracies. A trenchant reminder of that last point came yesterday as dozens of groups around the world solemnly commemorated the one year anniversary of the hanging of two boys in Iran just for being gay. Islamic Sharia law punishes homosexuality by execution, and in Iran boys as young as 15 and girls as young as 9 are eligible for execution. These two boys, who were around 15 and 16 at the time of their "crimes", were incarcerated for 14 months and beaten with 228 lashes before being hung. Could "religion" and "justice" possibly be more perverted than this savage villainy?

Understanding the tribulations our forebearers went through to establish this nation should make us appreciate all the more the great liberty that we enjoy here. This is put in stark contrast by thinking of those in the Middle East who are struggling to establish or defend democratic ideals against vicious enemies, and those who are living under oppressive theocracies. A trenchant reminder of that last point came yesterday as dozens of groups around the world solemnly commemorated the one year anniversary of the hanging of two boys in Iran just for being gay. Islamic Sharia law punishes homosexuality by execution, and in Iran boys as young as 15 and girls as young as 9 are eligible for execution. These two boys, who were around 15 and 16 at the time of their "crimes", were incarcerated for 14 months and beaten with 228 lashes before being hung. Could "religion" and "justice" possibly be more perverted than this savage villainy?

Understanding the tribulations our forebearers went through to establish this nation should make us appreciate all the more the great liberty that we enjoy here. This is put in stark contrast by thinking of those in the Middle East who are struggling to establish or defend democratic ideals against vicious enemies, and those who are living under oppressive theocracies. A trenchant reminder of that last point came yesterday as dozens of groups around the world solemnly commemorated the one year anniversary of the hanging of two boys in Iran just for being gay. Islamic Sharia law punishes homosexuality by execution, and in Iran boys as young as 15 and girls as young as 9 are eligible for execution. These two boys, who were around 15 and 16 at the time of their "crimes", were incarcerated for 14 months and beaten with 228 lashes before being hung. Could "religion" and "justice" possibly be more perverted than this savage villainy?

Understanding the tribulations our forebearers went through to establish this nation should make us appreciate all the more the great liberty that we enjoy here. This is put in stark contrast by thinking of those in the Middle East who are struggling to establish or defend democratic ideals against vicious enemies, and those who are living under oppressive theocracies. A trenchant reminder of that last point came yesterday as dozens of groups around the world solemnly commemorated the one year anniversary of the hanging of two boys in Iran just for being gay. Islamic Sharia law punishes homosexuality by execution, and in Iran boys as young as 15 and girls as young as 9 are eligible for execution. These two boys, who were around 15 and 16 at the time of their "crimes", were incarcerated for 14 months and beaten with 228 lashes before being hung. Could "religion" and "justice" possibly be more perverted than this savage villainy?

Tuesday, July 11, 2006

Another Plessy

I haven’t commented on the disappointing ruling from New York’s Court of Appeals last week, that denying same-sex marriage is rational, mostly because I have little to add to what others have already written. In case you missed it, the Court found that it is rational to induce straight people to marry because they’re irresponsible and might accidentally have children, while gay people only have children when they want to, so an extra state inducement to marriage is not needed. Kip, among others, gives a pretty good fisking of the decision. This will surely end up on the dungheap of judicial travesties, alongside Plessy v. Ferguson and its ilk. Except that it will probably become moot before it gets overruled. I also agree with Andrew that the proper response in New York is to shrug and start working on the legislative solution.

I thought the most intriguing analysis was from Jason Kuznicki, who explains why he thinks the Court got the rational basis test per se wrong. He caveats his analysis with the standard disclaimer that he’s not a lawyer, but in my opinion (not that I’m a lawyer either), Jason sure knows his constitutional law. He begins with the standard definition of the "rational basis test": that the Court must decide whether what the Legislature enacted is a rational means for achieving a legitimate government end. He then observes that the NY Court’s opinion analyzes whether the end was rational, not whether it was legitimate. And as a good libertarian, Jason is always quick to question whether a government end is legitimate. He makes a convincing case that the Court bungled the rational basis test in their analysis. Thus, it was NY’s Supreme Court that got the issue right. (Alas, in New York’s upside-down court nomenclature, the Supreme Court is not the supreme court.)

I thought the most intriguing analysis was from Jason Kuznicki, who explains why he thinks the Court got the rational basis test per se wrong. He caveats his analysis with the standard disclaimer that he’s not a lawyer, but in my opinion (not that I’m a lawyer either), Jason sure knows his constitutional law. He begins with the standard definition of the "rational basis test": that the Court must decide whether what the Legislature enacted is a rational means for achieving a legitimate government end. He then observes that the NY Court’s opinion analyzes whether the end was rational, not whether it was legitimate. And as a good libertarian, Jason is always quick to question whether a government end is legitimate. He makes a convincing case that the Court bungled the rational basis test in their analysis. Thus, it was NY’s Supreme Court that got the issue right. (Alas, in New York’s upside-down court nomenclature, the Supreme Court is not the supreme court.)

Sunday, July 09, 2006

Lessons from Mexico's Election

I read with interest a couple of pieces that appeared in the LA Times this weekend concerning the as-yet-unsettled election results in Mexico. First, Robert A. Pastor, an authority on elections and democracy, notes that Mexico has not only made huge strides in creating highly credible election institutions and procedures, it has surpassed the US in that regard. Mexico's Federal Election Institute (IFE), Pastor explains, is a non-partisan fully autonomous commission that runs Mexico's elections nationwide, and is widely respected and trusted (in a country which generally has a high degree of mistrust and cynicism in its own government). He notes the stark contrast between the corrupt elections he observed in Mexico 20 years ago, and the reliable process he observed last week, and then goes on to explain in detail the lessons that the US might now learn from Mexico, such as credible processes to insure that voter registration lists are accurate, that only registered voters vote, and only once. (One item Pastor left off of his list: though Mexico's election was very close and there will be recounts, there will be no "dangling chad" issues. Their election technology is not only standardized nationwide, but it is more modern and reliable than most of our own state-by-state and county-by-county hodge-podge.)

He concedes that the very close election will certainly test Mexico, but notes that "close elections are always dangerous" because a just-short-of-majority of people may be "resentful and angry." (He draws the obvious comparison to the US election in 2000.) We ultimately survived the election of 2000 because we have a long-established commitment to our democratic procedures. As a practical matter we generally all (excepting a few die-hard leftists) acknowledged Bush as our President, and nobody has seriously advocated overthrow of the government. But it was our tradition carried us through, not the credibility of our specific processes and election administration, which were shown to be sorely lacking. In Mexico, trust in democratic procedures is still nascent at best, and if their democracy survives this election, it will be on the strength of their electoral institutions (as well as the actions of the winner in working to heal the divide). I think Pastor is also right that the US could stand to learn from its neighbor as far as election administration goes. Look further than both these elections, there may well be lessons to be drawn from the US and Mexico in terms of the importance of institution and process versus trust and tradition that should be applied wherever we're attempting to "transplant" democracy onto foreign soil (as in Iraq).

Meanwhile, Gregory Rodriguez offers an intriguing assessment of Lopez Obrador (AMLO) as a potential threat to Mexico's democracy. AMLO seems intent on not accepting any result other than his own victory in the election. Rodriguez writes of AMLO:

He concedes that the very close election will certainly test Mexico, but notes that "close elections are always dangerous" because a just-short-of-majority of people may be "resentful and angry." (He draws the obvious comparison to the US election in 2000.) We ultimately survived the election of 2000 because we have a long-established commitment to our democratic procedures. As a practical matter we generally all (excepting a few die-hard leftists) acknowledged Bush as our President, and nobody has seriously advocated overthrow of the government. But it was our tradition carried us through, not the credibility of our specific processes and election administration, which were shown to be sorely lacking. In Mexico, trust in democratic procedures is still nascent at best, and if their democracy survives this election, it will be on the strength of their electoral institutions (as well as the actions of the winner in working to heal the divide). I think Pastor is also right that the US could stand to learn from its neighbor as far as election administration goes. Look further than both these elections, there may well be lessons to be drawn from the US and Mexico in terms of the importance of institution and process versus trust and tradition that should be applied wherever we're attempting to "transplant" democracy onto foreign soil (as in Iraq).

Meanwhile, Gregory Rodriguez offers an intriguing assessment of Lopez Obrador (AMLO) as a potential threat to Mexico's democracy. AMLO seems intent on not accepting any result other than his own victory in the election. Rodriguez writes of AMLO:

Indignant over his loss, he has accused Mexico's Federal Electoral Institute of "manipulating" votes. In so doing, he is not only impugning the credibility of one of the nation's most trusted organizations, he is encouraging the type of cynicism about politics that helped semi-authoritarian regimes maintain power in Mexico for most of the 20th century.Lopez Obrador has summoned his followers to rally in the Zocalo (the large central square in the capital) to protest the apparent election results which declared his opponent Calderón the winner. Whereas the protestors in the immediate wake of the 2000 US election were demanding to "count every vote", AMLO is all but saying he won’t accept a loss even if the recounts go against him. Rodriguez offers an insightful diagnosis here:

Because populism traditionally thrives in profoundly unequal societies where the dispossessed don't trust the system to solve their problems; where they turn, instead, to charismatic figures they hope will take on the state, defeat it and funnel its largesse away from the elite and toward the poor. They put their faith in leaders rather than in democratic processes. It's a recipe for authoritarianism.I have not been familiar enough with Mexican politics to have a strong opinion about the election, but I have to admit the Lopez Obrador’s behavior this week has certainly got me hoping that Calderón is ultimately declared the winner (and that AMLO hasn’t abused his influence too greatly in undermining Mexico’s fledgling faith in democracy).

Thursday, July 06, 2006

When Warfare was Genteel

In doing research on an ancestor who was in the American Revolution, I came across a bit of history that really struck me, showing how much more genteel an affair warfare was back then. To set the scene, it helps to understand that British ships of war were sitting in New York Harbor, Governor Tryon was a crown appointee and loyalist (and "governing" from the ships, as he didn't feel safe from the "patriot rabble" in New York City), the pilot house and light at Sandy Hook were strategic to the patriots, and the operator of the light, Adam Dobbs, was a patriot. With that background, consider this entry in the minutes of the New York Committee of Safety (the local patriot organization):

(Of course, it wasn't entirely genteel. The same Governor was implicated in a plot to kidnap George Washington.)

Amazing, isn't it? That would be like today in Iraq or Gaza or Sudan, somebody sending a message to their enemy saying in effect, "sorry we had to destroy your spy's base, but we didn't harm the spy or his family or things, and we'll promise safe passage for you to come in and retrieve him". Can you imagine?De Veneris, 10 HO, A.M.

A copy of the letter from Governor Tryon, to the Major of this city dated the 19th instant, was read. He thereby informs that the commanders of the King's ships, on this station, had thought it necessary to burn the pilot house near the light house. That proper care has been taken of Adam Dobbs and his family and effects, and that if a sloop is sent down to receive Dobbs, his servants and effects, she will be permitted to return safe.

April 26th 1776

(Of course, it wasn't entirely genteel. The same Governor was implicated in a plot to kidnap George Washington.)

Wednesday, July 05, 2006

Gelato Has Arrived!

I still remember the first time I tried gelato, the ultimate ice cream, when I visited Florence in 1980. Oh, sure I had eaten ice cream before, but this experience was transcendent. Cioccolata gelato at Vivoli was like sweet cocoa beans melting like butter on your tongue, and fragola at Perche No was like God implanting the pure essence of ideal strawberry-ness sensually but directly to your brain. For all the years since then, I have wondered why quality gelato is so hard to find. Gelato shops in the US have been extraordinarily rare - I'd only known one in Berkeley years ago, one still going in Palo Alto - otherwise you need to hop a plane and fly to Florence or Rome or Paris. (The renowned Berthillon calls their product 'glace' rather than 'gelato', but it's the same sublime stunningly-fresh-flavored substance. It is even said that France's glace can be traced to Catherine de Medici bringing gelato from Florence.)

Suddenly, gelato seems to be in vogue. In old town Pasadena, Tutti Gelati has been open for over year, making traditional flavors with ingredients and techniques imported from Milan. We've found ourselves going to movies more often at the Laemmle One Colorado just so we can have gelato afterward. Tutti Gelati is very good, but it does not quite hit the perfection of flavor found in the top European places (or in Gelato Classico in Palo Alto). It's very creamy and flavorful, but somehow a bit too much sugar and milk foils the maximal fruit and nut flavors shining through.

But now, just recently, a new gelato place has opened up practically in our backyard: Pazzo Gelato, on Sunset at Hyperion, in Silver Lake. And this, this is the real thing! My first encounter was with an almond fig gelato, and oh I could just taste those almonds melting on my tongue. Last week, a banana zabaglione gelato with a drizzle of caramel had me closing my eyes and moaning, savoring every spoonful. Each week the flavors vary, and it is hard to choose. (The owners buy their fruit at local farmer's markets, and the freshness is evident.) I tried a taste of rose gelato (yes, the flower!) which was extraordinary, and a Venezuelan chocolate sorbetto that was incredibly rich. Their sorbettos are amazing, well-stirred as they are crafted, so that there is no iciness to them, and some are even creamy (despite having no milk in them). My husband had a mango-cayenne sorbetto, a surprisingly effective combination (reminded me of the spices mixed with confection in the film Chocolat). Pazzo Gelato is fast becoming part of our Friday night routine. I only hope that this is not a fad that will blow away with the next change of season, but for now it has reinvigorated wonderful memories of my first gelato.

Suddenly, gelato seems to be in vogue. In old town Pasadena, Tutti Gelati has been open for over year, making traditional flavors with ingredients and techniques imported from Milan. We've found ourselves going to movies more often at the Laemmle One Colorado just so we can have gelato afterward. Tutti Gelati is very good, but it does not quite hit the perfection of flavor found in the top European places (or in Gelato Classico in Palo Alto). It's very creamy and flavorful, but somehow a bit too much sugar and milk foils the maximal fruit and nut flavors shining through.

But now, just recently, a new gelato place has opened up practically in our backyard: Pazzo Gelato, on Sunset at Hyperion, in Silver Lake. And this, this is the real thing! My first encounter was with an almond fig gelato, and oh I could just taste those almonds melting on my tongue. Last week, a banana zabaglione gelato with a drizzle of caramel had me closing my eyes and moaning, savoring every spoonful. Each week the flavors vary, and it is hard to choose. (The owners buy their fruit at local farmer's markets, and the freshness is evident.) I tried a taste of rose gelato (yes, the flower!) which was extraordinary, and a Venezuelan chocolate sorbetto that was incredibly rich. Their sorbettos are amazing, well-stirred as they are crafted, so that there is no iciness to them, and some are even creamy (despite having no milk in them). My husband had a mango-cayenne sorbetto, a surprisingly effective combination (reminded me of the spices mixed with confection in the film Chocolat). Pazzo Gelato is fast becoming part of our Friday night routine. I only hope that this is not a fad that will blow away with the next change of season, but for now it has reinvigorated wonderful memories of my first gelato.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)