A few memories of Tante Elayne. We called her “Tante”, which means “aunt” in French and German and Yiddish.

Tante was a proud New Yorker. Her heart never left New York, and neither did her voice. Both Tante and Unc lived her over 50 years and never lost their New York accents. We'd say, “Tante, we saw a hawk in our yard this morning.” “A what?” We'd show her the picture and she'd say “oh, you mean a hawwk. When you said 'hock' I thought you were talking about a piece of ham.”

Tante was a vocal right-winger. When asked about her politics, she'd smile and say “You know Attila the Hun? I'm to the right of him.” “My grandfather was a Republican,” she growled proudly, “he hated FDR even from when he was governor of New York.” Like Archie Bunker, she was blunt and not the least "politically correct", but like Archie, she was a lovable curmudgeon. Sunday night family dinners were always lively, as we knew well how to push each other's buttons. She was often outnumbered, but she always stood her ground.

Tante was not an early adopter of technology. It was ages before she was convinced to get an answering machine (not voicemail, mind you, but the machine with the cassette tape in it), and it was only a couple years ago she finally conceded to allow a microwave oven into her kitchen. “There's no room on my counter.” When the Fresh & Easy market went in down the street, with exclusively self-service check-out, the manager got to know Tante & Unc very well, because they'd always call him over and say “we don't know how to do this machine thing, you have to do it for us.” As inquisitive and interested in the news as Tante was, you would think she would love the Internet, but when we suggested it, she got such a pained, horrified look on her face. “What on earth would I do with the Internet?” She was content enough for us to bring our iPhones to Sunday dinner so we could show her pictures from Facebook of what her grandchildren were up to. And she'd ask us to look things up for her. Mostly about her favorite radio personalities. It's no small irony that we were hampered in sharing the Internet with Tante by the fact that this house is a total dead zone for AT&T, as if there's an anti-technology force field protecting the house.

Tante claimed to be anti-social. She didn't use that word, she had better SAT words. She taught me the word “dour” when I showed her a photo of some 19th century ancestors who looked particularly stern and forbidding. “Look at those dour expressions”, she said approvingly, “my kind of people.” If you asked her if she liked meeting people, she would say “no, dear, I am a misanthrope.” In truth, though, she would talk to anybody, and she loved getting people's stories. When we'd go out to eat, as soon as she finished, she'd excuse herself to go smoke a cigarette out behind the restaurant, and she'd often come back having met someone, and she'd have gotten their whole life story. She would meet friends of mine even just once or twice, and she'd interrogate them, learning things I didn't always know. She wasn't just being polite, she was interested, and she would remember. Not names, so much, but she'd remember stories. Even years after she'd met someone once, she'd ask about them -- whatever happened to your friend the architect, or that one with the young daughter with cataracts, how is she? Some misanthrope.

Tante loved eating. She ate with gusto. And she was a gracious guest. She would always compliment the meal, earnestly and enthusiastically. Even at our very casual Sunday family dinners, she would exclaim with delight about knockwurst and cabbage, as if she were trying the dish for the first time. Of course, my Mom's knockwurst and cabbage is really good. We all love it, but Tante was always the first one to say so. She had a gift for expressing appreciation. “Oh George, you're clearing dishes again, you don't have to do that, you're such a help.” “Oh Thomas, you brought me blueberries, I love blueberries, and so good for you!” A couple years ago, when they needed some extra help, their granddaughter Rachel chose to take her spring break out here helping them. Rachel, you must have heard that appreciation. We sure heard it afterwards. “Oh that Rachel, she's such a help! And such a good cook!” Part of that might have just been a good upbringing by Elayne's mother, who never left the house without her hat and gloves. But Tante always expressed her appreciation so heartily, as if you were the first person to ever clear a dish or bring her an apple. It was a gift, and a good lesson.

Sunday night dinners will never be the same without Tante oleha sholom, v zichronah livrakha (peace be upon her, and may her memory be for a blessing).

Monday, June 27, 2016

Tante Elayne -- Life Sketch

Elayne was born on Feb 18, 1931, in the Bronx, New York City, the daughter of Paul and Rhea Taylor. Her mother's side of the family, the Brantmans, were Jewish. Her grandparents, Louis and Betty Brantman, were eastern European immigrants who met in New York City, and re-enacted Fiddler on the Roof with their family of five daughters, each daughter pushing the boundaries of their father's traditional views a bit further. Paul Taylor, from a line of Taylors going back nearly to the Mayflower, and ancestry entirely English and Scottish, was obviously not Jewish, and not Louis' idea of a perfect match for his daughter, but when Paul agreed to study for two years to convert to Judaism, Louis consented to the match. When Elayne was born, her grandfather registered her birth in temple, where she was given the Jewish name Sarah.

Elayne was Paul and Rhea's first daughter. A year and a half later came Cecile, and for their whole lives, those two would be as close as any two sisters ever were. Their early childhood was the midst of the Great Depression, and their family was as hard hit as any. Paul was an accountant working in Manhattan, and in the late 1920s, when the stock market looked like it could only go up, he had put most of his and his family's money into it. When the girls were very young, Rhea's parents both passed away, and Paul moved his family to New Jersey, where they could be closer to Paul's parents, and his brothers Frank and Don. For a time, the whole extended Taylor family was sharing one house, but later in the 1930s, Paul found steady work at a casting company, and the family had their own home in Great Notch. The girls had a good time there, and used to play on the train cars parked at the station near their house.

By 1941, Elayne's father, who had gone to a military school, was eager to take his part in World War II. The US hadn't joined the war yet, so Paul went up to Canada and enlisted with the Royal Canadian Artillery, where he soon shipped out and spent the rest of the war in the European theater. Rhea, left alone with two young daughters, moved to an apartment in Kew Gardens in Queens, where she could be closer to her sisters Nina and Fanny, and their families. For a time, Aunt Fanny and Uncle Sam lived upstairs in the same building. Nina had two daughters, Carol and Betty, just a bit younger than Elayne and Cecile. After the war, Paul chose to stay in Canada rather than return to his family. Rhea, Elayne, and Cecile lived in that same apartment in Queens throughout the 1940s and most of the 1950s. Elayne and Cecile had happy teenage years there, spending time with family, attending Forest Hills High School, going to social events at the Jewish Community Center, and sometimes going in to the city with their mother, who reportedly never left the house without hat and gloves. When Elayne was about 20 years old, it was at one of those events at the Jewish community center that she met Harold Hess, the handsome elder son of a shopkeeper in Forest Hills. No one remembers exactly how long they courted. Unc Harold says "We met at the party, she invited me home to meet her mother, she was nice, and that was it." The one thing that Harold and Cecile both remember is that when Elayne brought Harold home to meet the family, he offered to fix a broken window shade, but ended up pulling the whole thing down on his head.

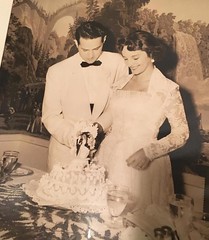

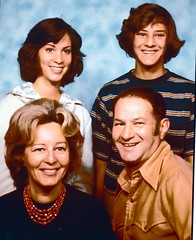

Elayne and Harold were married in August 1952, with a reception at the Forest Hills Inn, attended by family including all four of their parents. They moved into a small house on Harmony Drive in Massapequa on Long Island, nearby to her cousin Dottie Stetter and her young family. They enjoyed life in Massapequa, and made a lasting friendship with a neighboring family, the Amendolas. By the end of the 1950s, they had two children, Donna and Victor.

Meanwhile, Elayne's sister Cecile had moved out west, where she met her husband Rod Chatt, and settled in Granada Hills, where the suburbs of LA were just starting to push into the orange groves of the San Fernando Valley. Much as Elayne loved New York, she didn't want to be apart from her sister, and so in 1964, the Hesses moved to Granada Hills. They lived briefly in an apartment on Devonshire, and then moved into this house that is still their home after 50 years. Donna and Victor went to the elementary school right across the street, then Frost Jr High, and Kennedy High, which was built just in time for Donna to attend. The Hesses found more lifelong friends in this neighborhood, including the Hagawaras and the Hillbergs. (Like the Hesses, the Hillbergs are settled people, still here after 50 years.)

While Harold established his window-washing business, Elayne became quietly involved in the community, attending neighborhood watch meetings, and volunteering to be precinct captain of the local election board. But she mostly devoted herself to three great passions. One, she cleaned her house. Constantly. Her house was always immaculate. Two, she listened to conservative talk radio. She never quite warmed to the TV. The TV was fine for Masterpiece Theatre, for Jeopardy, and for Dancing with the Stars. But when it came to politics, for her, all the best people worth listening to were on the radio.

Elayne's third and greatest passion, of course, was rescuing animals. For the first 15 years they lived here, there was just a big open field from here to Balboa, at the end of the valley, a place where thoughtless people would dump unwanted pets. Her first rescue was Penny, an orange tabby who showed her love by bringing her mother trophies she'd catch in the field: birds, rats, gophers, all were no match for Penny. Elayne was particularly fond of Staffordshire bull terriers, more commonly known as the much-maligned "pit bull", and she took in several pit bulls over the years that had been mistreated by prior owners. When her house was filled with pets, she then filled her sister's house too. Many of the Chatts' pets were Elayne's rescues. And if you've seen their menageries, you know that clearly Donna and Victor have both inherited their mother's big heart for animals.

Elayne liked her life guided by routine. 9pm phone calls every night with her sister. Going out every Saturday night with the Chatts. Family dinner every Sunday at the Chatt or the Hess home. Getting together the whole family on Thanksgiving and Christmas. Visits every summer by Donna and her kids. I think she would like to be remembered simply, as faithful to her family, as a good neighbor and citizen, and as a lover of animals. And for 85 good years, that's exactly what she was.

|

| Elayne with her mother and sister |

By 1941, Elayne's father, who had gone to a military school, was eager to take his part in World War II. The US hadn't joined the war yet, so Paul went up to Canada and enlisted with the Royal Canadian Artillery, where he soon shipped out and spent the rest of the war in the European theater. Rhea, left alone with two young daughters, moved to an apartment in Kew Gardens in Queens, where she could be closer to her sisters Nina and Fanny, and their families. For a time, Aunt Fanny and Uncle Sam lived upstairs in the same building. Nina had two daughters, Carol and Betty, just a bit younger than Elayne and Cecile. After the war, Paul chose to stay in Canada rather than return to his family. Rhea, Elayne, and Cecile lived in that same apartment in Queens throughout the 1940s and most of the 1950s. Elayne and Cecile had happy teenage years there, spending time with family, attending Forest Hills High School, going to social events at the Jewish Community Center, and sometimes going in to the city with their mother, who reportedly never left the house without hat and gloves. When Elayne was about 20 years old, it was at one of those events at the Jewish community center that she met Harold Hess, the handsome elder son of a shopkeeper in Forest Hills. No one remembers exactly how long they courted. Unc Harold says "We met at the party, she invited me home to meet her mother, she was nice, and that was it." The one thing that Harold and Cecile both remember is that when Elayne brought Harold home to meet the family, he offered to fix a broken window shade, but ended up pulling the whole thing down on his head.

Elayne and Harold were married in August 1952, with a reception at the Forest Hills Inn, attended by family including all four of their parents. They moved into a small house on Harmony Drive in Massapequa on Long Island, nearby to her cousin Dottie Stetter and her young family. They enjoyed life in Massapequa, and made a lasting friendship with a neighboring family, the Amendolas. By the end of the 1950s, they had two children, Donna and Victor.

Meanwhile, Elayne's sister Cecile had moved out west, where she met her husband Rod Chatt, and settled in Granada Hills, where the suburbs of LA were just starting to push into the orange groves of the San Fernando Valley. Much as Elayne loved New York, she didn't want to be apart from her sister, and so in 1964, the Hesses moved to Granada Hills. They lived briefly in an apartment on Devonshire, and then moved into this house that is still their home after 50 years. Donna and Victor went to the elementary school right across the street, then Frost Jr High, and Kennedy High, which was built just in time for Donna to attend. The Hesses found more lifelong friends in this neighborhood, including the Hagawaras and the Hillbergs. (Like the Hesses, the Hillbergs are settled people, still here after 50 years.)

While Harold established his window-washing business, Elayne became quietly involved in the community, attending neighborhood watch meetings, and volunteering to be precinct captain of the local election board. But she mostly devoted herself to three great passions. One, she cleaned her house. Constantly. Her house was always immaculate. Two, she listened to conservative talk radio. She never quite warmed to the TV. The TV was fine for Masterpiece Theatre, for Jeopardy, and for Dancing with the Stars. But when it came to politics, for her, all the best people worth listening to were on the radio.

Elayne's third and greatest passion, of course, was rescuing animals. For the first 15 years they lived here, there was just a big open field from here to Balboa, at the end of the valley, a place where thoughtless people would dump unwanted pets. Her first rescue was Penny, an orange tabby who showed her love by bringing her mother trophies she'd catch in the field: birds, rats, gophers, all were no match for Penny. Elayne was particularly fond of Staffordshire bull terriers, more commonly known as the much-maligned "pit bull", and she took in several pit bulls over the years that had been mistreated by prior owners. When her house was filled with pets, she then filled her sister's house too. Many of the Chatts' pets were Elayne's rescues. And if you've seen their menageries, you know that clearly Donna and Victor have both inherited their mother's big heart for animals.

Elayne liked her life guided by routine. 9pm phone calls every night with her sister. Going out every Saturday night with the Chatts. Family dinner every Sunday at the Chatt or the Hess home. Getting together the whole family on Thanksgiving and Christmas. Visits every summer by Donna and her kids. I think she would like to be remembered simply, as faithful to her family, as a good neighbor and citizen, and as a lover of animals. And for 85 good years, that's exactly what she was.

Monday, May 30, 2016

Remembering Kathryn

On Saturday, a large crowd gathered at our church to remember our dear friend Dr. Kathryn Nelson Magarian. We were heartened (but not surprised) to see how many came, many from far away, to celebrate the life of a much beloved soul. Kathryn was one of those rare people who literally radiated joy and positivity. She beamed, often, with a room-lighting smile and a voice near song that made you feel like the most special person in the world, and she had the gift of making everyone feel special. When she met you, she would say that she was so glad to meet you, or so glad to see you, and she said it in a way that was so genuine and so not an automatic pleasantry that the words would strike you fresh, like you'd never heard them that way before, and you'd think "wow, she really is glad to see me!" At the end of church services, a crowd would always gather around her regular pew in the front-left, and her caregiver would have to wait patiently, as everyone wanted to spend a little time with Kathryn.

George and I first got to know her in 2008, when some mutual friends asked if we could give her a ride to their wedding in Redlands. Kathryn suffered from a degeneration of the cerebellum that gave her tremors and had made her unable to drive herself any longer. We were happy to oblige, and of course a long car ride can be a great way to get to know someone. She had lived a very full life and was full of great stories. She was recently retired from a 37-year career as a pediatrician at the White Memorial Hospital, having started as a legal secretary and then putting herself through med school in her thirties. She had traveled the world and been on great adventures, including hunting wild game in Africa (for the sake of spending quality time with her father, though she had the game trophies in her home to prove it). But as much as she had done and seen, she was also a great listener and eager to know all about us. At the end of that day, we knew we had made a great new friend.

There's an adage that one way to judge someone on a date is to see how they treat the waiter. Kathryn's contagious joy in people extended to everyone, and that was very clear if you ever took her to a restaurant that she had frequented before. All the staff would light up to see her, because they would all remember her, and she remembered them, often by name, knew their stories, asked about their families. Everyone was special to her, and made to feel special. In recent years, when she was spending more time in the hospital, it was the same story there. It was clear that all the nurses and staff had a special affection for Dr. Kathryn. At her memorial, Dr. Beth Zachary, the CEO of Adventist Health Southern California Region, spoke about how it was difficult just to move Kathryn around in the hospital, because they couldn't get very far down any hallway before they'd run into someone she had cared for as a doctor, and they'd light up to see her, and she'd light up to see them, remembering their names, their stories, their families, like they were the most special person in the world. As this remembrance was shared, hundreds of us smiled and nodded knowingly, having seen it ourselves.

Her radiant joy was a miracle in itself, but it was all the more amazing when I think about the great hardships she faced in her life. I'd mentioned the debilitating cerebellar degeneration. Recurrent cancers were piled on top of that. And she endured other brutal non-medical hardships I won't detail. She had more cause than most anyone to complain or to question her faith, and yet she did not do either. She remained unceasingly faithful in God, and unfailingly joyful in life. This loving woman, who probably would have loved to have had children of her own, was not given that. Yet when asked if she had children, she would reply with no sorrow and a genuine bright smile, "I was a pediatrician for 37 years, I have hundreds of children." And she adopted more as she went. We felt like she adopted us. That was just her nature to see the positive in everything, to find some cause for joy in each day, and to share it. Our world is a bit dimmer now without her light in it. She was an inspiration, and I hope I can honor her memory by striving to find joy in everything and share it with those around me.

George and I first got to know her in 2008, when some mutual friends asked if we could give her a ride to their wedding in Redlands. Kathryn suffered from a degeneration of the cerebellum that gave her tremors and had made her unable to drive herself any longer. We were happy to oblige, and of course a long car ride can be a great way to get to know someone. She had lived a very full life and was full of great stories. She was recently retired from a 37-year career as a pediatrician at the White Memorial Hospital, having started as a legal secretary and then putting herself through med school in her thirties. She had traveled the world and been on great adventures, including hunting wild game in Africa (for the sake of spending quality time with her father, though she had the game trophies in her home to prove it). But as much as she had done and seen, she was also a great listener and eager to know all about us. At the end of that day, we knew we had made a great new friend.

There's an adage that one way to judge someone on a date is to see how they treat the waiter. Kathryn's contagious joy in people extended to everyone, and that was very clear if you ever took her to a restaurant that she had frequented before. All the staff would light up to see her, because they would all remember her, and she remembered them, often by name, knew their stories, asked about their families. Everyone was special to her, and made to feel special. In recent years, when she was spending more time in the hospital, it was the same story there. It was clear that all the nurses and staff had a special affection for Dr. Kathryn. At her memorial, Dr. Beth Zachary, the CEO of Adventist Health Southern California Region, spoke about how it was difficult just to move Kathryn around in the hospital, because they couldn't get very far down any hallway before they'd run into someone she had cared for as a doctor, and they'd light up to see her, and she'd light up to see them, remembering their names, their stories, their families, like they were the most special person in the world. As this remembrance was shared, hundreds of us smiled and nodded knowingly, having seen it ourselves.

Her radiant joy was a miracle in itself, but it was all the more amazing when I think about the great hardships she faced in her life. I'd mentioned the debilitating cerebellar degeneration. Recurrent cancers were piled on top of that. And she endured other brutal non-medical hardships I won't detail. She had more cause than most anyone to complain or to question her faith, and yet she did not do either. She remained unceasingly faithful in God, and unfailingly joyful in life. This loving woman, who probably would have loved to have had children of her own, was not given that. Yet when asked if she had children, she would reply with no sorrow and a genuine bright smile, "I was a pediatrician for 37 years, I have hundreds of children." And she adopted more as she went. We felt like she adopted us. That was just her nature to see the positive in everything, to find some cause for joy in each day, and to share it. Our world is a bit dimmer now without her light in it. She was an inspiration, and I hope I can honor her memory by striving to find joy in everything and share it with those around me.

Sunday, April 10, 2016

Three Black Lives

Accepting the premise that Black Lives Matter, I figured I should be reading more about contemporary black lives, and so I picked up three very different memoirs, each essential reading in its own way. I started with How To Be Black, by Baratunde Thurston. Much of the book skewers the uneasiness of race consciousness in contemporary America, with satirical advice on topics like "how to speak for all black people" and "how to be black at the office". The satire is funny and sharp (as one would expect given Thurston's long career at The Onion), puncturing perceptions, making you think and laugh at the same time. Interspersed with the advice chapters, we get the fascinating story of Thurston's own life, growing up with a single mother in Washington DC during the height of crack, then being one of the few black kids at an elite private school and later attending Yale. And the third component of his book is a series of interview questions with what he calls his "black panel", a set of "experts" on being black (which included one white guy for a scientific control), who added another dimension with the fascinating diversity of their experiences. The questions were all great, but the most interesting one for me was "When did you first realize you were black?" This particularly struck me, since as a gay man, I had always assumed gays were unique among minorities in having to realize later in life that we are gay. But the question, while humorous, elicited some serious responses. Even though black kids always know they're black, many of them did remember particular experiences when they first realized that being black was more than just a skin tone, that it was a social category. The whole book was entertaining and gently illuminating.

From this light start, I then turned up the gravitas with Ta-Nehisi Coates' Between The World And Me, a memoir written in the form of a letter from a father to his teenage son, telling his son the things he needs to know about where his father came from and what it means to him being black in America today. Coates grew up in a really rough part of Baltimore, and describes at a young age learning the rules of the street just to avoid being stabbed or shot. He later went to Howard University, which he calls "the Mecca", and was enthralled with that center of black culture. He describes people he knew and who influenced him, and things he has experienced that instilled in him an understanding of the particularly breakable vulnerable nature of "black bodies" -- everything from minor but telling affronts to personally knowing a man who was shot by police basically for being black in the wrong neighborhood. Everything is grounded in his very personal experience, avoiding polemics or politics, and that makes it profoundly powerful. It's all what he saw, what he lived, and what he felt. Polemics invite debate, but experience has a raw truth with no place for debate. His intense missive is elevated by the words with which his experiences are described. His prose is masterful, emotionally vivid and evocatively poetic. It is truly a brilliant work of writing, and a must-read for anyone wanting to understand this experience. In Coates' book, he spoke of his complete alienation from the white suburban lives he saw on TV as a child, and of those suburbs being built on piles of "broken black bodies" by the "people who need to think of themselves as white". While I understood his feelings, he didn't really explain what he thought caused that situation, and I didn't understand it until Cory Booker spelled it out for me.

The third book I read was United: Thoughts on Finding Common Ground and Advancing the Common Good by Cory Booker, former mayor of Newark and now US Senator from New Jersey. His memoir is an inspirational story: we get some brief glimpses of his childhood growing up in one of the first black families to integrate themselves into the very white Harrington Park, New Jersey, and then attending Stanford, Oxford, and Yale Law School. The meat of the story starts with him as an idealistic newly-minted lawyer wanting to help improve the city of Newark, and getting a real hands-on education by choosing to live in one of the most crime-ridden parts of the inner city. He tells the story of Brick Towers, a 16-story housing complex built in 1970, initially a promising place to live, but ultimately dragged down by landlord neglect to suffer rat infestations and broken elevators, and its location in a neighborhood of the city effectively semi-abandoned by the City of Newark to become a center of drug dealing. In the years he lived there, he got to know just about everyone, and he tells the story of the indomitable woman who lead the tenants association, of parents and kids who live there, and even of the drug dealers who worked there. He gains and shares fascinating insight into who these people are and how they got to be where they are. This is all intermixed with his own story of how he went from being a public interest lawyer to city councilman and eventually mayor and senator. Some skeptics will say that his actions and his book are all politically self-serving, but I think he came across as genuinely concerned to improve his city and his country. Living in blighted housing for a few days or weeks is a publicity stunt; Cory Booker lived in Brick Towers for 10 years until it was torn down, and then he sought another crime-ridden area of his city to move to. I don't see how one can say that's not the real deal. I found his book inspirational, in terms of gaining a new understanding of deep social problems that suggest practical solutions, and in terms of the faith that drives him, a combination of religious faith and a faith in his fellow citizens to work together to find solutions. I think Cory Booker is a new hero for me.

From this light start, I then turned up the gravitas with Ta-Nehisi Coates' Between The World And Me, a memoir written in the form of a letter from a father to his teenage son, telling his son the things he needs to know about where his father came from and what it means to him being black in America today. Coates grew up in a really rough part of Baltimore, and describes at a young age learning the rules of the street just to avoid being stabbed or shot. He later went to Howard University, which he calls "the Mecca", and was enthralled with that center of black culture. He describes people he knew and who influenced him, and things he has experienced that instilled in him an understanding of the particularly breakable vulnerable nature of "black bodies" -- everything from minor but telling affronts to personally knowing a man who was shot by police basically for being black in the wrong neighborhood. Everything is grounded in his very personal experience, avoiding polemics or politics, and that makes it profoundly powerful. It's all what he saw, what he lived, and what he felt. Polemics invite debate, but experience has a raw truth with no place for debate. His intense missive is elevated by the words with which his experiences are described. His prose is masterful, emotionally vivid and evocatively poetic. It is truly a brilliant work of writing, and a must-read for anyone wanting to understand this experience. In Coates' book, he spoke of his complete alienation from the white suburban lives he saw on TV as a child, and of those suburbs being built on piles of "broken black bodies" by the "people who need to think of themselves as white". While I understood his feelings, he didn't really explain what he thought caused that situation, and I didn't understand it until Cory Booker spelled it out for me.

The third book I read was United: Thoughts on Finding Common Ground and Advancing the Common Good by Cory Booker, former mayor of Newark and now US Senator from New Jersey. His memoir is an inspirational story: we get some brief glimpses of his childhood growing up in one of the first black families to integrate themselves into the very white Harrington Park, New Jersey, and then attending Stanford, Oxford, and Yale Law School. The meat of the story starts with him as an idealistic newly-minted lawyer wanting to help improve the city of Newark, and getting a real hands-on education by choosing to live in one of the most crime-ridden parts of the inner city. He tells the story of Brick Towers, a 16-story housing complex built in 1970, initially a promising place to live, but ultimately dragged down by landlord neglect to suffer rat infestations and broken elevators, and its location in a neighborhood of the city effectively semi-abandoned by the City of Newark to become a center of drug dealing. In the years he lived there, he got to know just about everyone, and he tells the story of the indomitable woman who lead the tenants association, of parents and kids who live there, and even of the drug dealers who worked there. He gains and shares fascinating insight into who these people are and how they got to be where they are. This is all intermixed with his own story of how he went from being a public interest lawyer to city councilman and eventually mayor and senator. Some skeptics will say that his actions and his book are all politically self-serving, but I think he came across as genuinely concerned to improve his city and his country. Living in blighted housing for a few days or weeks is a publicity stunt; Cory Booker lived in Brick Towers for 10 years until it was torn down, and then he sought another crime-ridden area of his city to move to. I don't see how one can say that's not the real deal. I found his book inspirational, in terms of gaining a new understanding of deep social problems that suggest practical solutions, and in terms of the faith that drives him, a combination of religious faith and a faith in his fellow citizens to work together to find solutions. I think Cory Booker is a new hero for me.

Sunday, March 20, 2016

Most Influential Books

Thinking about books that have changed me, there are a few that go back to high school:

Books that affected my life from college days:

In the decades since college, I think a few books have had substantial impact on my life and/or influence on my thinking:

- Strunk & White's "The Elements of Style", for impressing on me that writing is a craft and a skill

- George Orwell's "1984", for impressing on me the power of words, and the importance of naming things correctly, and also that government can be corrupt

- Shakespeare's "Hamlet", for giving me an appreciation of the soaring heights of the best of the English language, as well as planting the seed that would flower decades later in a life quest to see all of Shakespeare's works, which was itself a pillar in one of the most important friendships in my life

- Plato's "Apology", for impressing on me the value of goodness and truth

- a book that I think was by Evelle J. Younger (Calif Attorney General in the 1970s) called something like "A Student's Guide to Legal Rights", which outlined the rights that students had (e.g., to refrain from pledging allegiance) and the constitutional principles and cases that established them, which gave me a lifelong love and fascination for constitutional law. (I can't remember the exact title or be sure of the author. I only know that I found it in the Petit Park branch of the LA Public Library in the 1970s.)

Books that affected my life from college days:

- Bertrand Russell's "Why I Am Not a Christian". Long before Hitchens or Dawkins had even been born, there was Russell. Not that I was ever a believer, but he was an early hero of the despised minority of atheists, clear in his arguments and forthright in his convictions.

- Jeffrey Stout's "The Flight From Authority", the text for a freshman year class that looked at the intellectual crisis that occurred post Reformation when knowing what was true was no longer a matter of asking the right authorities. It gave me a lifelong appreciation for a particular strand of philosophy that happened to find its home at Princeton in the Religion Department, introduced me to some professors who were profoundly influential to me, and acquainted me with a vital conversation in contemporary philosophy including Rorty, Alasdair MacIntyre, Stanley Hauerwas, and others.

- Richard Rorty's "Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature", a tour-de-force critique of post-Enlightenment philosophy

- the Fannie Farmer cookbook, for giving me the essentials to gain confidence in my own basic cooking skills, providing a foundation for a lifelong love of cooking.

In the decades since college, I think a few books have had substantial impact on my life and/or influence on my thinking:

- Andrew Sullivan's "Love Undetectable", for crystalizing the virtues of love and friendship and the value of being gay

- Ernest Hemingway's "For Whom The Bell Tolls", which taught me that a life well lived is not measured by its time span, and that love, even if fleeting, is worth having

- Nina Planck's "Real Food", which, along with Michael Pollan's seminal "Simple Rules" New York Times essay, really set me on the path of more locally grown, farmers market-driven, home-cooked eating.

- Jeffrey Stout's "Democracy and Tradition", which I read in 2008 during the Calif Prop 8 (anti-gay marriage) battle, and which took the philosophical dialogues I'd been following for years and gave them very practical application in how to address my fellow citizens about a vital and controversial issue

- Arnold Kling's "Learning Economics", which taught me not only the basics of economics, but the economic way of thinking (so that I was already predisposed to love Freakonomics when that came out)

- Andrew Sullivan's "The Conservative Soul", for showing me that "conservative" doesn't have to be synonymous with "selfish and judgmental" (and in a way, this book entry really is a proxy for Andrew's blog, which I read religiously for years and was enormously influential on me)

- Daniel Gilbert's "Stumbling on Happiness", for illuminating me about how fallible our cognitive processes are, and that one should plan with humility

- David McCullough's "1776", for giving me a proper sense of awe for how, had slightly different decisions been made at certain points, certain advice ignored or followed, certain unknown things discovered, or even the wind blown differently on a certain day, our fate could have been entirely different, and that the course of history is fragile. (His "John Adams" also gives me comfort, when I am despairing that our political polarization is worse than ever, that no, actually, it's not.)

- Malcolm Gladwell's "Outliers", for giving a vivid argument of how much we owe to our circumstances and our forebears

- Jared Diamond's "Guns, Germs, and Steel", for giving a visionary argument for how much we, on a biological and evolutionary scale, owe to our circumstances

Friday, March 04, 2016

Reflections on Antonin Scalia

I can say this about Scalia: the man knew how to wield a pen. His dissents were always colorful and entertaining, a guilty pleasure to read. How can one not appreciate someone who can drop words like "argle-bargle" and "jiggery-pokery" when brandishing his prose? It's unfortunate that this skill wasn't put in the service of better ends. In the annals of the Court, Scalia will be remembered for bringing the notions of "textualism" and "originalism" into currency. These are the ideas that correct judicial interpretation of the Constitution can be readily found by reading the plain words (textualism) and understanding the Founders' original meaning (originalism). They are meant to counter the notion that the Constitution is a "living document" that must be interpreted by the Court according to its essential principles in light of current understanding. Students of religion will recognize these theories as they apply to Biblical hermeneutics, and students of history will recognize how well the idea that one can gain universal agreement on the clear interpretation of the "plain words" (sola scriptura) works out. Taken at face value, Scalia's principles would have to rule that the Air Force is unconstitutional, as the plain text of the Constitution enumerates only an Army and a Navy, and the idea of military air power would not have been conceived of by the Founders. Though challenged on it, Scalia never did really explain how an originalist could endorse a decision like Brown v. Board of Education (the 1954 decision that ended school segregation), since the ratifiers of the 14th Amendment certainly didn't foresee or intend that implication themselves. His dodge is that he would have correctly decided Plessy v. Ferguson in the first place (that's the notorious 1896 case that ruled "separate but equal" schools constitutional). That's cheap hindsight. It's far more likely that an 1896 Scalia would have been as benighted by the prejudices of the day, finding segregated schools a reasonable social norm, as the present-day Scalia who heartily endorsed Bowers v. Hardwick (the infamous 1986 case upholding the constitutionality of sodomy laws). As called out in a New York Times opinion piece by Circuit Court Judge Richard Posner and law professor Eric Segall, Scalia is really a theocratic majoritarian at heart, content to find no power in the Constitution to protect minorities against the tyranny of the majority, at least when it comports with his own conservative morality. When his principles would seem to lead to a conclusion that went counter to his personal morality, his intellect and prose would be brought to bear to torture his principles into confessing the desired conclusion. See, for example, his opinion for the Court in Raich v. Gonzales, finding that Congress's Commerce power could regulate people growing pot in their own backyard for their own personal use, and Justice Thomas's dissent in a rare split from Scalia. Likewise, one might well wonder how a textualist or an originalist finds "corporate personhood" (the idea that corporations are persons, and thus have the same rights as persons) in the plain text or original meaning of the Constitution. While he refused to see the straight lines from the Founders' principles through de Toqueville and John Stuart Mill to landmark decisions like Griswold (finding a fundamental right to marital privacy that made it unconstitutional to outlaw contraception) and Lawrence (overturning Bowers and sodomy laws), he could see "penumbras" when he wanted to. Ultimately, he was as guilty of "interpretive jiggery-pokery" as anyone. His originalism may have provided better cover for his anti-gay animus, except that his apoplectic dissents on every landmark advance in gay rights over the last thirty years unabashedly laid bare his conservative moral prejudices. Despite the clear constitutional jurisprudence that "bare animus" is insufficient rationale for a discriminatory law (i.e., a majority may not outlaw a minority without a reason better than "ew that's weird"), Scalia, in his dissent in Romer v. Evans, rises to the defense of bare animus when it amounts to moral disapproval of homosexual conduct.

Beyond his legacy of originalism, he also leaves a legacy of coarsening the level of discourse around contentious issues, unfortunately now embodied in the records of our highest court, and emulated by many of his Federalist Society acolytes. The admittedly entertaining creativity of his prose often belied bare pugnaciousness, light on real argument. He was famous for his tart interrogations during oral arguments, and the zingers in his dissents. Here is a typical example in his stinging dissent in Obergefell (last year's landmark gay marriage ruling):

If, even as the price to be paid for a fifth vote, I ever joined an opinion for the Court that began: “The Constitution promises liberty to all within its reach, a liberty that includes certain specific rights that allow persons, within a lawful realm, to define and express their identity,” I would hide my head in a bag. The Supreme Court of the United States has descended from the disciplined legal reasoning of John Marshall and Joseph Story to the mystical aphorisms of the fortune cookie.This is just plain mockery of Justice Kennedy's opinion, with no particular "disciplined legal reasoning" of its own to offer. (One might claim that there is legal reasoning elsewhere in the dissent, but really, no, it's just one long rant about "judicial putsch" that could have been equally aimed at Lawrence or Griswold or Loving or even Brown.) If ever there were a time to hide one's head in a bag, I would think it would be after writing something so derisive and insulting about a colleague I'd be facing the next day (and working closely with for the rest of my life). Often it is only the cleverness of the prose that distinguishes Scalia's writing from the incivil name calling and insults found on the typical Internet comments page (or more recently, the Republican debates). One might consider him the Supreme Court's original troll. A few years ago, when he was speaking at Princeton, a gay student pointed out the language in some of Scalia's dissents that was especially offensive (such as comparing homosexuality to bestiality or pedophilia) and asked him, even if he still stood by his argument, if he had any regrets for his offensive choice of words. No, he did not. It is ironic that he worried he was witnessing the deterioration of our culture with the advance of gay rights (despite his best efforts to fight it at every opportunity), and yet by his own example he lead the coarsening of constitutional legal discourse and contributed to the erosion of respect for the institution he served. That being said, I will miss reading his dissents. There is the guilty pleasure of the zingers, of course. But the best part of reading a Scalia dissent is knowing that it was a dissent, and that despite his grandiloquent tantrums, liberty and justice prevailed.

Sunday, February 28, 2016

Remembering Gladys

This weekend, we celebrated the life of our friend Gladys, who passed away last week just two months shy of her 106th birthday. (Yes, that was not a typo. When Gladys was born in 1910, William Howard Taft was President, Edward VII was on the throne, and the fictional events of Downton Abbey's first season wouldn't happen for a couple of years yet.) I first met Gladys when George and I were dating, and he started bringing me to his church in Glendale, where Gladys and her husband Gene were stalwart congregants. Not only did they attend Glendale City Seventh-day Adventist every Saturday, as Gladys had grown up Adventist, but they also attended the Methodist church every Sunday, where Gene, now retired, had been a pastor. George had been going to Glendale City Church because it had quietly established a reputation as a safe and accepting place for gay Adventists, and had a growing gay attendance. There were a few rows in the rear center section that had become the "pink pews". Gladys noticed the growing group of members in those rows, and decided that she and Gene should be welcoming, and that they were going to sit with us. So this octagenarian double-church-going couple made it their mission to sit with "all those nice young men". They had a midwestern friendliness about them, and Gladys became like an adopted grandmother to all of us, greeting everyone with hugs and always checking in on us, and asking after anyone who had missed a week or two. She had a sweet, grandmotherly way of cupping your face in her hand. Then after this had gone on some time, an awkward conversation happened. Gladys said to one of the guys, "you know, some people in this church have been spreading malicious gossip that you boys are all homosexuals, but I told them it's not true, and they shouldn't talk about 'my boys' like that." To which came the reply, "Um, Gladys, actually it is true." This threw her in a quandary. She was torn between what she had been taught about homosexuality and sin, and "her boys" whom she had come to love. She had a long talk with our pastor, telling him "I'd always been taught that it's wrong, but they're wonderful young men and I just can't reject them." She decided that "loving the gays" was her calling, which she undertook with zeal for the rest of her long life. She adopted us and we adopted her, and love made us all family.

Sunday, January 03, 2016

Six Feet Under

My latest "TV" binge watch (on my iPad) has been Six Feet Under, to catch up on the last two seasons that I never saw. Fittingly, on New Year's weekend, I watched the series finale. I had heard that it was extraordinarily well done, and that is so true. It was an amazing ride with the barely functional Fisher family, and I have to admit that there were times that I wondered whether I really liked any of these characters, even to the penultimate episode. But then in the final episode, life found a way to go on after a death that had affected them all, and it was so organic and so affirming. And then the final montage was simply wondrous. Structurally it combined two cinematic cliche endings — a ride off into the horizon and a roll call of every character and what happened to them — and yet it did it in such a fresh, profound way that it was extraordinary and luminous. The whole premise and structure of the series has been one long memento mori, a family-run funeral home with each episode beginning with a death, with characters often imagining conversations with the dead, constant reminders that life can be fleeting and death can be senseless. So it was brilliantly fitting that in the final montage we see the deaths of all the major characters, some sooner, some later. This span of lives over decades is telegraphed in flashing glimpses, interspersed with shots of Claire driving out of Los Angeles, away from the only home she's known, into a frightening, exciting, beckoning unknown future unfolding like the highway before her disappearing into the horizon, and all to the beautifully haunting song "Breathe Me" (Sia Furler). She's just learned her job offer in New York has been rescinded, but her dead brother urges her to go anyway, not to live in fear. And as she takes a farewell photograph of her family, Nate whispers in her ear "the moment is already gone, you can't capture it." Moments and lifetimes. What an exquisite piece of television, and what a perfect note on which to begin a new year.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)