Early Sunday morning we got the call that we'd been reluctantly expecting. George's father, George Sr., had passed away, quietly and at home. He had been declining for the past week or so, no longer eating, and we knew that the end was approaching. He was 88 years old, and he leaves behind his wife of 60 years, a son, a daughter, three sons-in-law, two grandchildren, several nieces and nephews, and numerous loving friends and relatives.

Early Sunday morning we got the call that we'd been reluctantly expecting. George's father, George Sr., had passed away, quietly and at home. He had been declining for the past week or so, no longer eating, and we knew that the end was approaching. He was 88 years old, and he leaves behind his wife of 60 years, a son, a daughter, three sons-in-law, two grandchildren, several nieces and nephews, and numerous loving friends and relatives.I've known George for seven years, and at the same time I never really got to know him. He had suffered a stroke a year or two before I met him, and although he still had his mind and his voice, he had lost a great deal of mobility, and was a much more subdued man than he had been. The only George I got to know directly was an elderly man who lived in a hospital bed set up in his home, aside from occasional wheelchair excursions to church, to his daughter's home, or to his own dining room for larger family gatherings. I'm not sure what he thought about me, this guy who just started showing up with "Georgie" (as my husband is known in his family to distinguish from his father) to all the family gatherings, but he seemed to just accept me. I was always greeted with a handshake, and was always included by name when he asked the blessing before a family meal (I was always touched by that). We never talked about much, as he was not long on conversation. He could hear and understand well enough, and could give appropriate answers, but he would usually say just enough to answer, and it was apparent that it was an effort to produce the words. Conversation with George really depended on the visitor to hold up most of it. My brothers-in-law could rally longer than I could, as they shared his interest in golf and football. (Me discussing the SF Giants is a painfully short conversation.) I have few memories of him initiating a topic of conversation. When he did, it was usually a paternal concern about the safety of our travel: "How was the road? You be careful. The road's dangerous." (It was sweet that he worried about us. Our mention in grace was usually along those lines too: "thank you Lord for bringing George and Tom safely to us".) Such was the George I got to meet personally. But it was very clear that that George was but a shadow of the George who had lived a good full 80 years before the stroke. That other George was someone I only got to know indirectly, in the reflected light of his family's stories, of old photos and films, of the traits he instilled in his children and the traits he shared with his siblings, and of the evidence of his community contributions.

To explain my understanding of who George was, it's necessary to back up and describe his home town, the town he lived in from age 2 until last Sunday. Lodi lies in central California's San Joaquin Valley, farming heartland. Though today it looks more like a growing suburb of 60,000+ residents, you don't have to drive far to see the vineyards and orchards that tell its deep agricultural roots. When the Scheideman family moved to Lodi in 1921, the population was a few thousand. Just a couple years earlier, at a parade for returning World War I veterans, A&W Root Beer was first sold (for a nickel at a roadside stand). It was the kind of American town Normal Rockwell would have recognized. A few things gave Lodi its distinct character: German immigrants, Seventh Day Adventists, and flame tokay grapes. The first German immigrants settled in Lodi in 1897, and many followed in the early decades of the 20th century. George's family moved there from Kansas. His father, also George, grew up in Kansas, but was actually born in the village of Norka, a German colony on the Volga River deep in Russia. (George B. Scheideman, as he was known in America, was actually christened as Johann Georg Scheidemann.) His mother, Rachel Reuscher, was born in Kansas, but both of her parents were also from Norka. The Scheidemans came, children, parents, grandparents, aunts and uncles, cousins, along with many other German immigrant families of similar origins. Into Lodi they brought their values of hard work, self reliance, strong close families, and tight-knit communities. And their devotion to their Christian faith, with their church being the center of their community. In particular, they were Seventh Day Adventists. I haven't figured out how they got involved in Adventism (which was an American innovation, and certainly not something they brought with them from the old country), but it is clear that the growth of the Adventist church in Lodi was linked with the growth of the German community. The first Adventist services in Lodi were held in a home in 1905, the first church was built the next year, and by 1908 a second church was built which became the "English" church, as the first church became the "German" church. In those early years, the services were all in German, and it wasn't until 1942 that they completely switched to English. Adventism is more than a religion, it is a culture, and many of its values -- close families and communities, strong generational ties and traditions -- fit perfectly with the German immigrant values. And to those family values, Adventism made its own unique contributions, including its distinctive emphasis on health, and on careers of service. An amazing proportion of Adventists go into a health or teaching profession (or both). It's a calling, often reinforced by family tradition. Find an Adventist community, and you're bound to find a school and a hospital. Thus Lodi Academy was founded in 1908 as a boarding school. The hospital would come later, in 1952, as these first generation German-immigrant Adventists were not doctors, they were farmers.

And they took root and flourished in Lodi's fertile soil. Many things were farmed in Lodi, including wheat, watermelons, and fruit orchards, but the local pride was the Flame Tokay grape, a varietal nearly unique to the Lodi area. It is said that the variety developed its distinctive "flaming red" hue in Lodi's soil, and the skin of that grape grown elsewhere does not attain that color. The Flame Tokay was traditionally a table grape. It has good "structure" for wine (that is, a good balance of high sugar and high acidity), but a fairly neutral flavor, making it best suited as a blender in fortified or sparkling wines, rather than a standalone wine varietal. Those who know the taste of this grape prize it, but alas in the present day it is nearly extinct commercially, as the market for table grapes with seeds is nearly vanished. Meanwhile Lodi has cultivated a reputation for excellent zinfandel in recent years, leading local vineyards to rip out the old tokay vines and plant the more profitable zin instead. But in any case, for over a century, Lodi has been all about the grape. (One Lodi public high school is Tokay High, and Lodi High's team is the Flames.)

And they took root and flourished in Lodi's fertile soil. Many things were farmed in Lodi, including wheat, watermelons, and fruit orchards, but the local pride was the Flame Tokay grape, a varietal nearly unique to the Lodi area. It is said that the variety developed its distinctive "flaming red" hue in Lodi's soil, and the skin of that grape grown elsewhere does not attain that color. The Flame Tokay was traditionally a table grape. It has good "structure" for wine (that is, a good balance of high sugar and high acidity), but a fairly neutral flavor, making it best suited as a blender in fortified or sparkling wines, rather than a standalone wine varietal. Those who know the taste of this grape prize it, but alas in the present day it is nearly extinct commercially, as the market for table grapes with seeds is nearly vanished. Meanwhile Lodi has cultivated a reputation for excellent zinfandel in recent years, leading local vineyards to rip out the old tokay vines and plant the more profitable zin instead. But in any case, for over a century, Lodi has been all about the grape. (One Lodi public high school is Tokay High, and Lodi High's team is the Flames.) Thus, George grew up the youngest of two sons and three daughters, on a vineyard on Stockton Street, with his grandparents on their vineyard on the same street. (According to the 1930 census, the Scheidemans owned their own farms, as one would expect of this self-reliant hard-working immigrant stock.) A bio of George would later say, "his father was a vineyardist, and George was raised with a thorough background in farming a vineyard." In other words, he was not unacquainted with digging an irrigation ditch, pruning a vine, or harvesting the grapes by hand using a small curved knife as they did it back then. Come September, one would expect the whole family to be involved in the harvest. The good Adventist parents made sure the children all got a good education. George graduated from Lodi Academy in 1938, and went on to attend Pacific Union College (an Adventist college in Angwin, California, just above the Napa Valley) and Stanford University. When the US entered World War II, the Scheideman family answered the call to civic service. George enlisted on 30 Jan 1942, and his brother Lee enlisted 6 months later. His sister Doris served as a nurse, and even his father registered at age 55. George served in the US Army medical corps, with much of his service in the China-Burma-India theater of war, in the 71st Field Hospital. He said it was like the TV show MASH, except much more transient and portable. (I once asked George what India was like, and mostly what he recollected was that it was oppressively hot.)

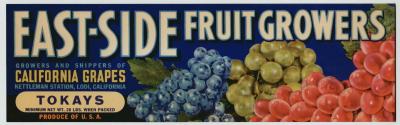

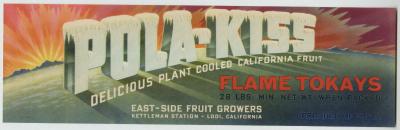

Thus, George grew up the youngest of two sons and three daughters, on a vineyard on Stockton Street, with his grandparents on their vineyard on the same street. (According to the 1930 census, the Scheidemans owned their own farms, as one would expect of this self-reliant hard-working immigrant stock.) A bio of George would later say, "his father was a vineyardist, and George was raised with a thorough background in farming a vineyard." In other words, he was not unacquainted with digging an irrigation ditch, pruning a vine, or harvesting the grapes by hand using a small curved knife as they did it back then. Come September, one would expect the whole family to be involved in the harvest. The good Adventist parents made sure the children all got a good education. George graduated from Lodi Academy in 1938, and went on to attend Pacific Union College (an Adventist college in Angwin, California, just above the Napa Valley) and Stanford University. When the US entered World War II, the Scheideman family answered the call to civic service. George enlisted on 30 Jan 1942, and his brother Lee enlisted 6 months later. His sister Doris served as a nurse, and even his father registered at age 55. George served in the US Army medical corps, with much of his service in the China-Burma-India theater of war, in the 71st Field Hospital. He said it was like the TV show MASH, except much more transient and portable. (I once asked George what India was like, and mostly what he recollected was that it was oppressively hot.) After the war, George returned to Lodi where he successfully combined his college studies of business administration with his background in farming. With his partner Luke Tonn, he founded the East Side Fruit Growers, a cold storage and fruit shipping business. The storage plant, adjacent to a railroad siding at Kettleman Station in Lodi, enabled the fruit of Lodi's vineyards and orchards to be shipped by train to more distant markets. The East Side Fruit Growers established itself as a brand, along with other trade names such as "Pola-Kiss" emphasizing the freshness offered by their cold storage, which was state-of-the-art for the time. Their colorful labels marked many a fruit shipping crate.

After the war, George returned to Lodi where he successfully combined his college studies of business administration with his background in farming. With his partner Luke Tonn, he founded the East Side Fruit Growers, a cold storage and fruit shipping business. The storage plant, adjacent to a railroad siding at Kettleman Station in Lodi, enabled the fruit of Lodi's vineyards and orchards to be shipped by train to more distant markets. The East Side Fruit Growers established itself as a brand, along with other trade names such as "Pola-Kiss" emphasizing the freshness offered by their cold storage, which was state-of-the-art for the time. Their colorful labels marked many a fruit shipping crate.  George made his trade not by farming himself, but as an "agri-businessman". He would buy farmers' crops in advance on contract, taking on the risk of whether it would be a good or bad year, but then owning all the upside market potential. His involvement in the local grape-growing industry lead to his service as a Commissioner of the California Table Grape Commission from 1968-1985. In his early years on the Commission, he had his work cut out for him, as the reputation of table grapes had suffered from the boycotts organized by the United Farm Workers, even after a labor contract was reached and the boycott officially called off in 1971. George often appeared on TV news programs when they wanted the viewpoint of the grape farmer. In 1979 he sold East Side Fruit Growers, and became "semi-retired", although he continued to be involved in the local grape business. He was recognized by the Lodi District Chamber of Commerce as Agriculturist of the Year for 1981, a commendation that was echoed in a resolution by the California Assembly.

George made his trade not by farming himself, but as an "agri-businessman". He would buy farmers' crops in advance on contract, taking on the risk of whether it would be a good or bad year, but then owning all the upside market potential. His involvement in the local grape-growing industry lead to his service as a Commissioner of the California Table Grape Commission from 1968-1985. In his early years on the Commission, he had his work cut out for him, as the reputation of table grapes had suffered from the boycotts organized by the United Farm Workers, even after a labor contract was reached and the boycott officially called off in 1971. George often appeared on TV news programs when they wanted the viewpoint of the grape farmer. In 1979 he sold East Side Fruit Growers, and became "semi-retired", although he continued to be involved in the local grape business. He was recognized by the Lodi District Chamber of Commerce as Agriculturist of the Year for 1981, a commendation that was echoed in a resolution by the California Assembly.  George's career was impressive, but even more impressive are the many ways he served his community. It seems like every time I visited Lodi, I would learn of another civic institution that George was involved in. We would see the physical "fruits" of his service all over town. "There's the bank that Dad was on the Board of Directors of," my husband would point out. On another trip, "there's the hospital. Dad was Chairman."

George's career was impressive, but even more impressive are the many ways he served his community. It seems like every time I visited Lodi, I would learn of another civic institution that George was involved in. We would see the physical "fruits" of his service all over town. "There's the bank that Dad was on the Board of Directors of," my husband would point out. On another trip, "there's the hospital. Dad was Chairman."And the school board. And the church. It was amazing. There was the Farmers and Merchants Bank of Central California. It's one of the major banks in the greater Lodi area, and during the years that George served on the board of directors, the bank expanded out of Lodi and into nearby communities of Galt, Elk Grove, and Stockton. Such was their respect for him that they asked George to stay on the board for a couple of years after his stroke. Then there's the hospital. In 1952, Lodi Memorial Hospital was established, named in honor of fallen World War II veterans. George served on the hospital board from the late 1960s thru the 1980s, and was Chairman from 1982 to 1987.

During his tenure on the board, the hospital undertook several significant expansions, including an $8.5 million expansion adding 47,000 square feet (about a 50% increase in capacity) in 1982. While George was Chairman, the hospital successfully transitioned into the era of intermediary payors like Blue Cross and HMOs, and remained viable at a time when many hospitals were failing (Medicare and Medicaid were chronically underfunded in the 1980s, driving hundreds of hospitals under). Then there's the school. George was chairman of the school boards for both the Lodi SDA Elementary School and the Lodi Academy. George's children attended the Academy, as he himself had. (It's the sort of place long on family tradition, where the parents of your classmates were probably classmates of your parents. And the Scheideman family originally came to Lodi so their children could attend the Academy.) The Academy originally included a boarding school, with its own dairy and printing press, but times changed and demand for the boarding aspect decreased. By 1968, Lodi Academy was exclusively a day school. In recognition of his accomplishments and contributions, George was named Lodi Academy Alumnus of the Year in 1992. Then there's the church. George was a lifelong member of the Fairmont SDA Church (or its previous incarnations as the Lodi-German church and the Hilborn church). The present church on Fairmont Avenue was dedicated in 1960, and underwent major renovations in 1993. George served on many church committees over the years, including the Building committee (which his father had also served on) overseeing the church's construction and renovation. It should come as no surprise that George was also a longtime member of the local Rotary Club.

During his tenure on the board, the hospital undertook several significant expansions, including an $8.5 million expansion adding 47,000 square feet (about a 50% increase in capacity) in 1982. While George was Chairman, the hospital successfully transitioned into the era of intermediary payors like Blue Cross and HMOs, and remained viable at a time when many hospitals were failing (Medicare and Medicaid were chronically underfunded in the 1980s, driving hundreds of hospitals under). Then there's the school. George was chairman of the school boards for both the Lodi SDA Elementary School and the Lodi Academy. George's children attended the Academy, as he himself had. (It's the sort of place long on family tradition, where the parents of your classmates were probably classmates of your parents. And the Scheideman family originally came to Lodi so their children could attend the Academy.) The Academy originally included a boarding school, with its own dairy and printing press, but times changed and demand for the boarding aspect decreased. By 1968, Lodi Academy was exclusively a day school. In recognition of his accomplishments and contributions, George was named Lodi Academy Alumnus of the Year in 1992. Then there's the church. George was a lifelong member of the Fairmont SDA Church (or its previous incarnations as the Lodi-German church and the Hilborn church). The present church on Fairmont Avenue was dedicated in 1960, and underwent major renovations in 1993. George served on many church committees over the years, including the Building committee (which his father had also served on) overseeing the church's construction and renovation. It should come as no surprise that George was also a longtime member of the local Rotary Club. My husband had always described his father as a grape farmer, but when we were putting together the obituary for the newspaper, his mother objected to describing him as a farmer. "He wasn't a farmer," she insisted, "he was an agri-businessman." I see her point. But I think in a metaphorical sense, he really was a farmer. But he didn’t farm grapes so much as he "farmed" the grape business. And he tilled his community as a farmer tills the soil. In fact, George "planted" a lot of things in the fertile soil of Lodi's community, and made them flourish. He was a farmer of community institutions. He cultivated a bank, a hospital, two schools and a church. (Those were not vines he himself planted, but he cultivated the old vines that had been planted before him, and made them thrive and produce new fruit.) And he cultivated a family. He sustained a loving and devoted marriage of 60 years, and he raised three children in whom he cultivated the Adventist German-immigrant farmer values that had been bred into him. I'd say he truly was a farmer of Lodi.

My husband had always described his father as a grape farmer, but when we were putting together the obituary for the newspaper, his mother objected to describing him as a farmer. "He wasn't a farmer," she insisted, "he was an agri-businessman." I see her point. But I think in a metaphorical sense, he really was a farmer. But he didn’t farm grapes so much as he "farmed" the grape business. And he tilled his community as a farmer tills the soil. In fact, George "planted" a lot of things in the fertile soil of Lodi's community, and made them flourish. He was a farmer of community institutions. He cultivated a bank, a hospital, two schools and a church. (Those were not vines he himself planted, but he cultivated the old vines that had been planted before him, and made them thrive and produce new fruit.) And he cultivated a family. He sustained a loving and devoted marriage of 60 years, and he raised three children in whom he cultivated the Adventist German-immigrant farmer values that had been bred into him. I'd say he truly was a farmer of Lodi.