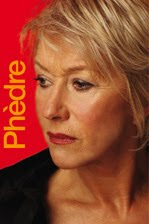

Sometimes I am incredibly lucky, and last night was one of those times. I had heard about the (British) National Theatre's production of Racine's Phèdre, lead by Dame Helen Mirren, which was causing sensations in London, and was coming to the US for twelve performances only, in Washington DC. I figured that would be one of those great events I'd just have to hear about from others. But then I was in Washington for a business trip this week, discovered it was the same week Phedre was in town, and thanks to CraigsList and some help from a good friend, I was able to score a ticket. I paid a premium, but it was so worth it. The play is a classic tragedy, coming from the ancient Greek drama Hippolytus by Euripides, adapted by the 17th century French master playwright Racine, and translated into modern English by poet Ted Hughes. The simple but beautiful set for this production echoes that pedigree. Racine's version all takes place in a single setting, in the palace of Troezen, with one side open to the sky, allowing his characters to literally move in and out of the light. Director Nicholas Hytner remains true to that concept, realizing the palace as a floor and ceiling of travertine, with a large hunk of rough travertine covering an exit, and a brilliant blue sky off to the right. To an Angeleno, the giant travertine tiles immediately conjure the Getty Center, an allusion which hits the perfect note of a modern reflection of ancient Greece. The tragedy is raw by modern standards, a roller-coaster of pity and horror, unleavened by lighter moments, driving inexorably to its horrible end. Histrionic speeches vividly express passion and anguish along the way. It's not a modern mode, but the Hughes translation in Hytner's hands felt Shakespearean, with hints of Edward Albee. And the remarkable cast brings it home.

Sometimes I am incredibly lucky, and last night was one of those times. I had heard about the (British) National Theatre's production of Racine's Phèdre, lead by Dame Helen Mirren, which was causing sensations in London, and was coming to the US for twelve performances only, in Washington DC. I figured that would be one of those great events I'd just have to hear about from others. But then I was in Washington for a business trip this week, discovered it was the same week Phedre was in town, and thanks to CraigsList and some help from a good friend, I was able to score a ticket. I paid a premium, but it was so worth it. The play is a classic tragedy, coming from the ancient Greek drama Hippolytus by Euripides, adapted by the 17th century French master playwright Racine, and translated into modern English by poet Ted Hughes. The simple but beautiful set for this production echoes that pedigree. Racine's version all takes place in a single setting, in the palace of Troezen, with one side open to the sky, allowing his characters to literally move in and out of the light. Director Nicholas Hytner remains true to that concept, realizing the palace as a floor and ceiling of travertine, with a large hunk of rough travertine covering an exit, and a brilliant blue sky off to the right. To an Angeleno, the giant travertine tiles immediately conjure the Getty Center, an allusion which hits the perfect note of a modern reflection of ancient Greece. The tragedy is raw by modern standards, a roller-coaster of pity and horror, unleavened by lighter moments, driving inexorably to its horrible end. Histrionic speeches vividly express passion and anguish along the way. It's not a modern mode, but the Hughes translation in Hytner's hands felt Shakespearean, with hints of Edward Albee. And the remarkable cast brings it home.  Helen Mirren's Phèdre exposes palpable passion and anguish (Phèdre is hopelessly in love with her stepson, knows how horrible that is, and struggles to avert it), verging on madness and suicide, her voice modulating loud and soft, high and low, expressing the waves of emotion in her character. And at times she speaks volumes just with a slight movement of her body. When she learns that Hippolytus loves another woman, a tightening of her body and a turn of her head vividly convey to the audience the emotional bullet she's just received, while revealing nothing to her husband. Dominic Cooper as Hippolytus captures the scope of that noble tortured character, forswearing love but then falling in love with the exiled daughter of his father's enemy. When fatally wronged by his father, he refuses to vindicate himself in order to spare his father the even-worse truth. Hippolytus keeps much bottled up, but Cooper's excellent portrayal succeeds in conveying the emotions within the reserved exterior, and the cost of maintaining that reserve. Other standout performances included John Shrapnel as Theramene, old counselor to Hippolytus, who rises to great Shakespearean proportions in the climax when he recounts the death of Hippolytus; and Ruth Negga as Aricia, the noble princess who drags in the remains of Hippolytus in the end (like Stevie in the third act of Albee's The Goat). The performance was breathtaking from start to horrifying finish.

Helen Mirren's Phèdre exposes palpable passion and anguish (Phèdre is hopelessly in love with her stepson, knows how horrible that is, and struggles to avert it), verging on madness and suicide, her voice modulating loud and soft, high and low, expressing the waves of emotion in her character. And at times she speaks volumes just with a slight movement of her body. When she learns that Hippolytus loves another woman, a tightening of her body and a turn of her head vividly convey to the audience the emotional bullet she's just received, while revealing nothing to her husband. Dominic Cooper as Hippolytus captures the scope of that noble tortured character, forswearing love but then falling in love with the exiled daughter of his father's enemy. When fatally wronged by his father, he refuses to vindicate himself in order to spare his father the even-worse truth. Hippolytus keeps much bottled up, but Cooper's excellent portrayal succeeds in conveying the emotions within the reserved exterior, and the cost of maintaining that reserve. Other standout performances included John Shrapnel as Theramene, old counselor to Hippolytus, who rises to great Shakespearean proportions in the climax when he recounts the death of Hippolytus; and Ruth Negga as Aricia, the noble princess who drags in the remains of Hippolytus in the end (like Stevie in the third act of Albee's The Goat). The performance was breathtaking from start to horrifying finish.As the play unfolded, I realized that I had seen a performance of the original Euripides tragedy that it was based on (a few years ago at the newly reopened Getty Villa). It hadn't hit me right away, as Racine's play is called Phèdre, while Euripides' play is called Hippolytus. But that just begins to tell the ways in which Racine shifted the focus and changed the play. The story is nearly the same in its outline, but in Euripides, Hippolytus is the tragic hero, cursed by the goddess Aphrodite because he spurns her in favor of Artemis, while Phaedra is an innocent pawn of the goddess, who kills herself before acting on her feelings. Racine turns the focus of the play on Phèdre, making her more culpable (though influenced by her Machiavellian nurse), and making Hippolytus more noble, and also adding the new wrinkle of Aricia, giving Hippolytus a forbidden love of his own. In Euripides, the goddesses actually appear in the play, and actively intervene in events, while in Racine, the gods are off-stage and the humans are undone by their own passions and flaws. A great drama stands the test of time, carrying its truth even as it is reinterpreted by different generations. In some ways, this play seems ancient, but at the same time, we read its echoes in recent headlines. Makes me wonder whether Racine should be my next quest. And I'll certainly keep an eye out for other National Theatre productions. Theatre of this caliber is worth going to lengths to see. (And apparently there's a new venture afoot at National Theatre to do live broadcasts of some of their productions to cinemas around the world. Check out NT Live.)

No comments:

Post a Comment